SEPTEMBER 23rd 2023

Merilyn Chang is a journalist and digital media manager based between New York and Berlin. She’s studied comparative literature and creative writing for her bachelor’s and has since been working on her first novel. Her work has been published by Dazed, Resident Advisor, Fact Mag and more.

Orison

Walk back with me to the green house no one lives in anymore.

Thursdays always taste grey and red, but for you, it was my

favorite day. When we spent most nights walking and the furthest

we’d ever made it was between three pieces of land all wedged together

like cars on Madison Avenue. We talked about

Running around a desert in north Asia, on prairies or tall grass,

Sleeping in tents. I saw all the stars but I couldn’t capture it on a camera.

We sat 10 feet away from the tent, in my mind, on a black blanket.

You laid down, your head close to my hip and you put your right hand on my lower back.

We don’t kiss or anything, yet. It would be just warm enough for a light

jacket in late August, except we were both in different places.

And other people were there too, in our minds.

But you were still in mine, every day. Every day I think about cooking pork

on your stove top that was covered in burnt char from the days before.

Everyday, the raspberry vitamin drink you made me and the mold

growing in the blender and the rain that day, before we walked to the

atrium style train stop, before you called my name under the underpass and it echoed in threes,

cascading off the walls. Cars fettered water in our direction but we didn’t care.

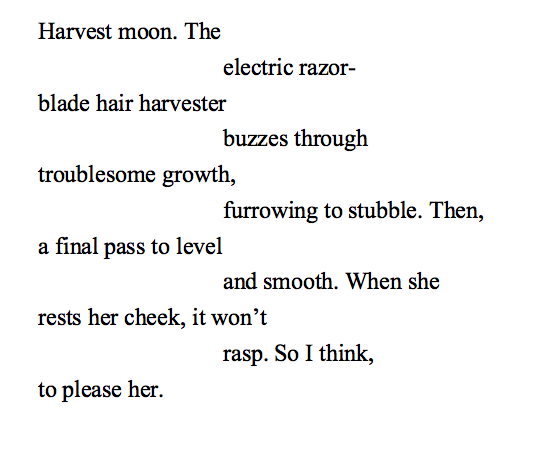

Think of a gentle without cold. And hands trimming facial hair. We

are not tender because we choose to be but because we would not be,

without tenderness. Slice the lemons so thinly and I’ll play an augmented seventh

on the Rhodes against the wall. You liked dissonances and my favorite part is the

Resolve after the muddle. The ray of light that comes when you stand in the perfect

position under a bed of leaves sounds like a fifth after six black keys.

At night we sleep and Jeff Buckley plays sweet harmony.

All my blood for the sweetness of her laughter. It’s never over. He hangs brightly

and breathes lightly. My sweet. Sugar plum. We never made it there.

Summer would be rolling on wood floors, hands dancing around the metal

pull-chain of a ceiling fan. But autumn was for strawberry sheets, waiting for a

relapse in the summer. In the green house where no one lives anymore, the landlords

upstairs say prayer at 5 in the morning, as we come home and unload stands

and gear and quietly walk up stairs that became drums in a song.

Think of me fondly. In November, send sweet songs and dissolved melodies.

Missing was never complete as much as it was a reach for completion.

Loving is only done out of survival but sometimes it feels enough to throw a car in the water.

Complete me dear, for I don’t think you could ever complete me. But glasses

still hold water, and trains still run east. The dining room table is still

covered in green from last night’s feast. All you can remember.

Can I tell you something? We were in the part of the dream, now

where the world was ending and the ground was orange, the sky was lilac.

There were palm trees outside the window, glowing green. I was in the part

Of the library with every single book ever written. A man sat at the

center in a suit. Told me I could read. And I looked down and you messaged me.

Do you know what you asked? You asked if I remembered the last time

we kissed. The dream ends there and I wake up and it is my birthday

and three days ago I was tripping on something that kept me up till

10 in the morning, and I thought of walking again to the green house.

Sweep old contact shells from the floors and pick at cold blades of the AC

vent. Lay me down, and bring in the utensils that beg for meat to cut into.

But don’t cut into it. Think of the whole that comes from mercy.

Sometimes I watch old videos of you and freeze the frame right when the

light hits your eyes and I remember the way you looked at me the third time

I saw you. You have stars in your eyes, sometimes. I am giving you the spoon now

and asking you if you will please wash it twice. I am holding the blue to the light

while you stand on chairs. I am, again, in the part of the Dream where the world is ending

and I am walking east out of the library under the palm trees

wondering if you’ll meet me. The grass has grown slightly.

And the air smells like rain from October four years ago.

~

SEPTEMBER 4th 2023

William Ross is a Canadian writer living in Ontario. His poems have appeared in Rattle, Bluepepper, Humana Obscura, New Note Poetry, Cathexis Northwest Press, and Topical Poetry. Recent work is forthcoming in *82 Review, Heavy Feather Review, and The New Quarterly.

Thanksgiving

Someone

chalked a faint moon in the sky

in broad daylight.

Somebody

shattered the sun

and threw the glittering shards across the night.

These things happened long ago,

before you were in the world, before

two someones created you.

On a cloudless day,

we visit their graves high above the

harbour water in Burlington Bay,

we light the incense, and bow three times

in respect and remembrance,

and I thank them for the gift of their daughter.

~

Abed

the rain

the rain

a song percussive

and gentle

on the roof

it wraps us

in a soft sadness

as we lie

and listen

and breathe

drawn closer

we fall too

we fall

~

FEBRUARY 6th 2023

Tom Veber (1995, Maribor) is an artist, who works at the junction of theatre, music, visual arts and literature. His poems were published in Croatia, Hungary, Greece, France, Austria, Germany, Russia and China. His poems are published in two collection The breaking point published in 2019 by Literarna družba Maribor publishing house, and in collection Up to here reaches the forest, published last year by ŠKUC – Lambda.

***

Your skin has a scent

of New York in the fall

when low clouds descend

over the narrow city streets

and you try to answer all questions

affirmatively

since you suspect the departure within yourself

and departures are always softer

in flocks of white lies

your eyelashes remind me

of narrow birch tips in Québec

in that park

where you held my hand for the first time

in that moment

I could assert with certainty

that my knees

melted into clouds

like in some Renoir painting

your protruding collarbones

paint the picture of the sharp Moher cliffs

of Western Irish shores

do you remember how whale backs

reflected the light

at sunset

like live mirrors

how the salty wind

stroked our flushed cheeks

how we laid down in the grass

and for hours stared

at each other

at the soft sky.

~

***

I am leaning against the window sill

my gaze is meandering around the city

I see some movements

some strokes into loneliness

I alternately sip green tea with rice milk

and smoke your cigarettes

I wait standing wide

I am greedily shrinking up

I am puffed up like a cat

before an attack

I shiver with everything

that can break

in a matter of seconds

I wait for you

continuously louder

you observe me

in ambush

your eyes scrape

across my heated body

you aim

you press

you shoot.

~

JANUARY 2nd 2023

Yeng Pway Ngon (1947-2021) was a Singaporean poet, novelist and critic in the Chinese literary scene in Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. A prolific writer, Yeng’s works have been translated into English, Malay, Dutch, and Italian.

阳光

你比我早起

在我窗外好奇地张望

你悄悄攀进来

爬上我的床,静静躺在

我身边

你的手指拂过我的身躯

如拂过

一排破旧的琴键

你的耳语

你的体温

你的甜蜜

令我哀伤

(20/5/2019)

The Sun

You wake up earlier than me

glancing around curiously outside my window

stealthily you climb

onto my bed lying beside me quietly

Your fingers run through my body

as if running through

a row of broken piano keys

Your whisper

your warmth

your sweetness

sadden me

~

DECEMBER 26th 2022

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Cleo Adler holds a B.A. in English and an M.A. in Comparative Literature. She writes poetry, essays, and reviews about travel and introspection, memory, and music. Published in Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Voice and Verse Poetry Magazine, Tentacle Poetry, and Literary Shanghai. She works between archives and libraries.

Three Questions

‘L’ is a sly and sluggish sound crawling out from the tip of the tongue,

as in ‘lax’, ‘listless’, and ‘nonchalance’, where ‘nonchalance’

is the mask worn by men whose tongues curl back

and roll out an ‘r’ in a matter of milliseconds that measures their effort.

How many words can we learn humming Simon and Garfunkel songs?

With my ears, I almost feel by touch their mouths stretch,

lured to suck their smacking lips and gnawing teeth.

I’ll never make their tongue mine,

but mine can coil around theirs and glide along slippery waves.

When I was four, I hated drawing curves so much that I cried

when copying the number ‘3’ ten times but

in my youth, I flaunted cursive writings in my homework.

It’s a tempting exercise to sketch a map of a walnut

since there’s no single way of making out its furrows.

How I dream of claiming it my laurel.

What good do words do?

They think theirs open up a meadow of daffodils

where you see the sun in a new light.

I say they are a desert where what we do is walk in circles

because that’s how our body works, the same way

my skin is tanned and my tongue is stiff.

Everyone prefers sunshine that’s brighter, warmer, more upfront,

but what I covet is one I’ll never be, nor be a part of

— although it grows in me—

for all my pestering and whining,

for the sake of the sense or eros.

Are words a fish or a fish trap?

It’s not about how to get the fish and forget the trap.

I have trouble with spelling, so to me,

a nicely woven basket does little harm; what I want to

forget is the fancy that with it a fish will be given.

At the river near where I live, there are men who

catch fish and put them into large foam boxes.

The next moment, they toss them to egrets.

Let us go fishing there one day.

~

OCTOBER 24th 2022

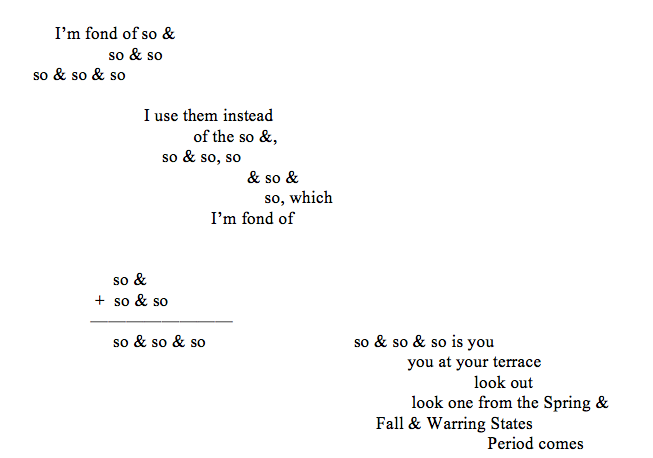

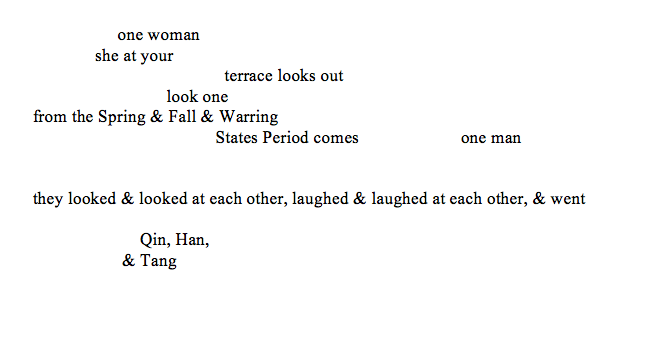

Yuan Changming hails with Allen Yuan from poetrypacific.blogspot.ca. Credits include 12 Pushcart nominations & 14 chapbooks, most recently Homelanding. Besides appearances in Best of the Best Canadian Poetry (2008-17), BestNewPoemsOnline & Poetry Daily, Yuan served on the jury and was nominated for Canada’s National Magazine Awards (poetry category).

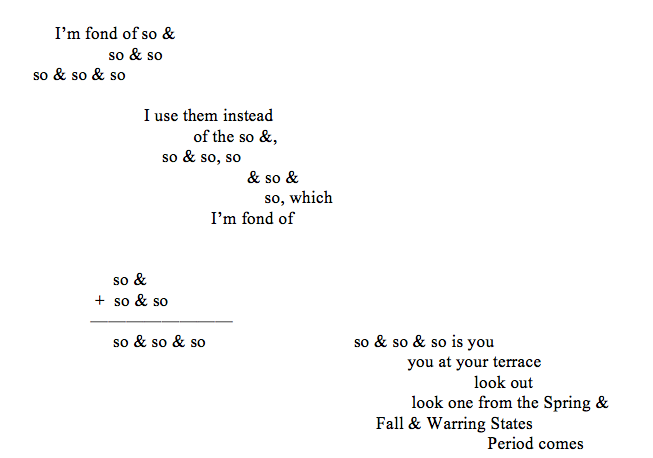

A Triword Poem: for Qi Hong & All Other Separated Lovers

to get(her) to-gather

~

Siamese Stanzas: Snowflakes

~

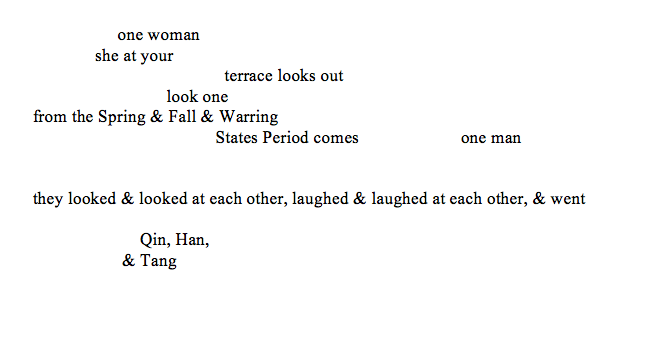

Love Lost & Regained: 2 One-Sentence Poems for Qi Hong

1/ Love Lost: a Rambling Sentence

How I sometimes wonder

Whether it is because you wear

Your years so well or because the years

Wear you so well that I fell in mad love with

You after as long as 42 years of separation without

Knowing each other’s whereabouts, again at first sight

With the whole Pacific Ocean between our shortening arms

2/ Love Regained: a Periodic Sentence

At a fairyfly-like moment

On a bushy corner of nature

Preferably under a tall pine tree

In Mayuehe, our mecca or the hilly village

Adjacent closely to the bank of the Yangtze River

With myriad tongues from my hungry innermost being

Each eager to reach deep into your heart, where my soul’s

Fingers could caress every single synapse of your feminine feel

Between the warmth & tenderness of love, across the Pacific & the Pandemic

I’ll join you

~

I/我 as a Human: a Cross-Cultural Poem

1/ Denotations of I vs 我

The first person singular pronoun, or this very

Writing subject in English is I, an only-letter

Word, standing upright like a pole, always

Capitalized, but in Chinese, it is written with

Seven lucky strokes as 我, with at least 108

Variations, all of which can be the object case

At the same time.

Originally, it’s formed from

The character 找, meaning ‘pursuing’, with one

Stroke added on the top, which may well stand for

Anything you would like to have, such as money

Power, fame, sex, food, or nothing if you prove

Yourself to be a Buddhist practitioner inside out

2/ Connotations of Human & 人

Since I am a direct descendant of Homo Erectus, let me stand

Straight as a human/人, rather than kneel down like a slave

When two humans walk side by side, why to coerce

One into obeying the other as if fated to follow/从?

Since three humans can live together, do we really need

A boss, a ruler or a tyrant on top of us all as a group/众?

Given all the freedom I was born with, why, just

Why cage me within walls like a prisoner/囚?

~

Lesson One in Chinese Character/s: a Bilinguacultural Poem about Heart

感:/gan/ perception takes place

when an ax breaks something on the heart

闷: /men/ depressed whenever your heart is

shut behind a door

忌:/ji/ jealousy implies

there being one’s self only in the heart

悲:/bei/ sorrow comes

from the negation of the heart

惑:/huo/ confusion occurs

when there are too many an ‘or’ over the heart

忠:/zhong/ loyalty remains

as long as the heart is kept right at the center

恥:/chi/ shame is the feel

you get when your ear conflicts with your heart

怒: /nu/ anger influxes when slavery

rises from above the heart

愁: /chou/ worry thickens as autumn

sits high on your heart

忍:/ren/ to tolerate is to bear a knife

straightly above your heart

忘: /wang/ forgetting happens

when there’s death on heart

意: /yi/ meaning is defined as

a sound over the heart

思: /si/ thought takes place

within the field of heart

恩: /en/ kindness is

a reliance on the heart

~

Directory of Destinies: a Wuxing Poem

– Science or superstition, the ancient theory of the Five Elements accounts for us all.

1 Metal (born in a year ending in 0 or 1)

-helps water but hinders wood; helped by earth but hindered by fire

he used to be totally dull-colored

because he came from the earth’s inside

now he has become a super-conductor

for cold words, hot pictures and light itself

all being transmitted through his throat

2 Water (born in a year ending in 2 or 3)

-helps wood but hinders fire; helped by metal but hindered by earth

with her transparent tenderness

coded with colorless violence

she is always ready to support

or sink the powerful boat

sailing south

3 Wood (born in a year ending 4 or 5)

-helps fire but hinders earth; helped by water but hindered by metal

rings in rings have been opened or broken

like echoes that roll from home to home

each containing fragments of green

trying to tell their tales

from the forest’s depths

4 Fire (born in a year ending 6 or 7)

-helps earth but hinders metal; helped by wood but hindered by water

your soft power bursting from your ribcage

as enthusiastic as a phoenix is supposed to be

when you fly your lipless kisses

you reach out your hearts

until they are all broken

5 Earth (born in a year ending in 8 or 9)

-helps metal but hinders water; helped by fire but hindered by wood

i think not; therefore, I am not

what I am, but I have a color

the skin my heart wears inside out

tattooed intricately

with footprints of history

~

JUNE 27th 2022

DS Maolalai has received nine nominations for Best of the Net and seven for the Pushcart Prize. His poetry has been released in three collections, “Love is Breaking Plates in the Garden” (Encircle Press, 2016), “Sad Havoc Among the Birds” (Turas Press, 2019) and Noble Rot (Turas Press, 2022).

Machinery moves.

lowering their winches,

cranes toil

and hoist skyward. the city

ticks taller, as mountain

and glacier-

spun time. from the top of this hill

and across the horizon

machinery moves

in a restful

slow motion,

swinging its balance

like the fat backs of spiders,

tucking untidiness

to the corners

of maps.

Daydrinking

it’s good – drinking wine

on these hot afternoons

on these days when we have

to be nowhere. we sit on the porch

at our second-hand table

and watch people walking

and coming from markets;

pushing strollers and pulling

at dogs. we get up and make

toast; bring it out with some ham,

old roast chicken and freshly

cooled bottles. occasionally

come out with coffee

or tonic on ice. white wine

all summer like snowmelt

from alleys; as yellow as suns

through the rise of the smoke

from that factory over the river.

as yellow as corn and as rippling

in pour as a field of it flowing to breezes.

you lean back, exhale, pull

at ivy which clings to our brickwork.

I look at your neck in the arc

of its stretching, like a cat standing up

on the back of a torn-apart couch.

Him.

it’s not that I’m an atheist

really – just don’t

want Him coming

to my wedding.

for christ sake –

it’s important to me

but that’s not the same

as Important –

not in the way

of a famine, of floods

running streets. He’s got better

to do (given grand schemes

and everything). if He’s real

then I shouldn’t take

his time. and if people maybe

stopped inviting Him

so often to weddings

then maybe He’d

stop making sunsets

so wonderful for them.

stop making birdsong

and mountains and rainbows

and other tacky garbage

for people to admire.

prevent some disease

and stop killing the innocent;

let’s get Him less lyrical.

put Him to work.

Maj 7th

we are in the back of this bar

up in phibsborough centre,

near the bohemian grounds.

he is back for a wedding –

we are getting a drink

and waiting for friends

to come meet us.

he talks about life now

as it happens near

amsterdam – has been studying

law there a year. talks about girls

and then tells me my scar’s

looking well – I must have

my own stories. I touch it – my finger

runs fishhook to eyebrow. feels folds

in the skin where the stitching

made crumples and seam. it’s true –

I look dashing when light

falls at angles. my eyes arch

and spiral, as if to a maj

7th chord. he rolls up

a cigarette, licks paper,

lights up and hands it to me

when I ask. it’s a light beerish saturday

evening in dublin. there’s a stretch

to the weather and clothes

have been drying on lines.

25 feet

my balcony faces a bicycle shop.

people come by with bicycles – men

pick them up, twist their spanners,

test tensiles, pump wheels.

hand cash out for bicycles,

trade like hard cattlemen. a ten

year old girl sits on top of a white/pink

and spun apart engine. kicks forward

and rolls up the pavement

quite slowly and wobbling for 25 feet.

behind her, her father stands

next to the salesman. they watch

as she goes and comes back.

~

JUNE 20th 2022

DS Maolalai has received nine nominations for Best of the Net and seven for the Pushcart Prize. His poetry has been released in three collections, “Love is Breaking Plates in the Garden” (Encircle Press, 2016), “Sad Havoc Among the Birds” (Turas Press, 2019) and Noble Rot (Turas Press, 2022).

A settle of saturday morning

breakfast with baker

by fegans in the settling

feathers of saturday.

mostly clear, though the sky

drops occasional spatters

of rain out of grubby

grey clouds; a fumbling toss

of a ten penny coin. we are both

having coffee. I’m eating,

jack’s waiting on breakfast.

two tables over, a french couple kisses

with hands in each others’

jeans pockets. it’s may

now – the summer has sparked

a good light out, like all of the lighters

outside all the bars

every evening at 7 o’clock.

like lights outside cafes at 11am

between french girlfriends’ fingers

and in waitresses hands on a break.

a pigeon walks under the table

and picks at a dropped piece

of bacon. it steps around ash

and is fat grey and silver.

it’s remarkably clean

for a bird.

Some flattery.

“look”, I said eventually –

he’d caught out the lie

about something I’d put

in the cover –

“I don’t want to sound

as ungrateful as I think

this will sound,

but it’s not as if anyone

really reads poetry.

of course I still hope

you should take

both the poems,

and take where I mentioned

my rising respect

for your press and achievements

as an editor

with the implication

it might be

some flattery. it’s not

as if either of us

hoped our careers

would involve some small magazine

printed way out in sligo. well,

maybe you did – I’m sorry;

I had aspirations.

and it’s not either

that I don’t

really want you

to publish me –

just, you know, you should

know that, given the option

I’d have gone probably

with faber

or someone

else first. shit.

wouldn’t anyone?

they pay.”

Nature will do things

the last guy who lived here

grew garden potatoes

and carrots. now flowers sprout up

in that corner each spring – all white

and bright yellow,

like tropical frogs

climbing stems.

I have let them go wild,

but nature will do things,

even when left

out untended. once

a goose landed,

falling like knocked-

over furniture. pawed about,

biting at seedlings and dandelions

while I stood by the door jamb

drinking water and watching it move.

Freedom, unpredictable.

kids in august summer

and sunning the park – just like dogs;

so unpredictable! and I never know,

walking from work,

what they are going to do

next – if they are going

to yell something

or kick a football at me. and yet,

it’s all so fine – it’s freedom, unpredictable

and I’m not feeling threatened.

I was like that myself once, though in my mind

I haven’t changed much

in 15 years, beyond perhaps gaining

a tolerance for alcohol.

it comes especially

when I see people I went to school with

at that age; like a brick

falling out of a house, I remember being part

of a whole

structure. the one

from when we all

were holding each other. it’s strange.

and yet, I was not an animal,

and they are not

either;

more like flowers. like when you drop seeds

in the garden and forget about them,

trying to make a meadow. staying inside

for weeks. the strong ones surviving, the weather

all closed. one day you open your door

and outside it’s all poppies,

grown and rained on. wet to a height

of five feet, perhaps more.

Manifesto

theme grows like plants

out of eaves, out

of gutters and fascias. it is not

laid like bricks – it’s not planned,

it is natural leaf. theme turns

to the sun and from dirt

in the corners of structure.

I cannot stand gardens. love dandelions,

thistles and daisies. divisions

on motorways, hemlock

wild garlic and nettles where rats

can lurk, biting and pissing.

the space between pavements

where people pass walking

and don’t look around, look ahead.

~

FEBRUARY 21st 2022

Xing Zhao is a writer and translator. He has written about contemporary art, culture, design, travel, and LGBTQ for publications including Architectural Digest, The Art Newspaper, Time Out, and OutThere. He is interested in ideas such as memory, exile, elsewhere, and displacement. He lives in Shanghai — a city that is not his home and writes in English — a language other than his native tongue. He is working on a collection of short stories and a long story, both with sentiments that permeate his poetry.

I Smell Him

I smell him

on me,

on the blue-black corduroy jacket

I’m wearing,

in the back of the closet where it’s hiding.

His smell stays with me

as though he was sitting next to me,

eyes

behind his thick black-framed glasses

a quiet gleam,

lips fluttering

are wings of a butterfly

dancing in a rainforest of luminous green.

What is he thinking? I think,

his mind is a storming sea,

drawer inside drawer

insider drawer

to which I do not have a key.

Mandalorian, Skywalker, and Jedi,

KAWS, The North Face, and Noguchi.

Words pour out of him and

I feel dizzy.

I wish

he’d stop speaking.

Does he know

I’m not at all listening?

The jacket

is the color of night

where blue enters black

and black becomes blue,

nocturnal animals sing songs,

rivers run across fields.

Lingers the smell of him,

of green moss grown on spruce

the morning after rain,

of ink smudged

on fingers,

of bergamot

blent into black tea,

of tobacco and stubble,

of him sitting at the bar of the coffee shop

when the barista says,

“He looks so clean.”

I want to know

if he knows

that he smells of rain,

of spring,

of a white T-shirt

billowing on a line in the wind,

of arms wrapped around my back

squeezing so tight

I hear a crackle in my spine.

In his jacket,

do I smell of him?

knowing his knows,

thinking his thoughts,

feeling how he feels,

when he’s sitting across the table,

our legs so close

they are almost touching,

when I lean over his shoulder and

pick up the book he’s reading,

when we walk side by side

to the park,

coffee in hand,

the sun is gold,

when he so casually hands me his jacket

the color of night,

the scent of fire,

and says,

“Yours it is.”

~

Green Island

My eyes are full of blue,

my heart is full of blue,

in this seaside town where

sky is made of glass and

waters are turquoise,

people cool as sea breeze.

You beam your twinkly eyes

in this dazzling midday sun,

I have springs to my steps

looking for my coconut drinks.

You say, “This is like Europe,” and

I say, “It is Malaya.”

On this island of green,

palms idly swing.

~

OCTOBER 25th 2021

Russell Grant is a poet from Durban, South Africa, living and working in Shanghai. He teaches high school English Literature and is the leader of the Inkwell Shanghai Poetry Workshop, as well as Head of Workshops for Inkwell Shanghai. His work has appeared in A Shanghai Poetry Zine and the Mignolo Arts Center’s journal Pinky Thinker Press.

After the Fact

– for the fallen at Zhengzhou

There is water in the creek, and in the sky,

and on his face, he who I watch from above

striding abreast the flow which

lumbers towards the Huangpu, mounted

by creek birds that hole up in the day

like forgotten promises.

He lumbers, too,

sucking at anxious air; drawing ancient breath;

burdened: 70% water, 30%

fermented fruit and guilt

The surface of the creek bristles in the rising wind

while a ginger cat suspends its cool indifference

to chase down shelter

in a vacant guard hut.

To the West a father

mounts a placard at a subway station exit,

sometime after the fact

and waits for her.

Above this, above all of this,

again the coiling sky spits, weeps

on towers, on parks, on runners and bikes,

on leaves loosened from their trees and

scattered on the concrete,

on the fathers of drowned daughters,

and on ginger street cats bristling in the wind

like the ruined surfaces of creeks.

~

Double-slit Experiment

- A sonnet for K, who helped me see again

Sunlight on the river blinks,

tracing waves both endless, and startless:

I observe their immaculate leaps

up from pregnant nothingness to sudden

bright peaks

shedding all possible past and future ways.

At night I trace your sleeping breath

like a pilot mapping your tireless rhythm

guided along all possible decisions

coming finally on gasping reality to rest:

Please forgive me my delayed noticing

and allow us sweetly in this moment to collapse

into a warm and most unambiguous

darkness. To settle the score between known and perhaps

and denounce all possible worlds but one

so we may find stillness before our breathing is done.

~

Longing

- A Daoist Ode to Condiments

Longing is the sauce of all unhappiness

She said, the clock adjusting like an uneasy guest

I search for a complement to your ungarnished bliss

Be like water, sufficient and saltless

Add nothing to the heartless breast

Longing is the sauce of all unhappiness

I grow weary of your philosophied spareness

Is there really no additive, no further drop to test

my resolve to find a complement for your ungarnished bliss?

Be like water, sufficient and saltless

Add nothing to the heartless breast

Longing is the sauce of all unhappiness

My deepest want, my soberest wish, is

that you quiet, please, this damned request

Longing is the sauce of all unhappiness

I long for an antedote to your ungarnished bliss

~

OCTOBER 18th 2021

Melvin Tan is a writer from Singapore. Years ago, he found himself asking: “If I die in my sleep, what is the one thing that I want my friends to remember?” Poetry, he decided. He never looked back. The fact that he has never been to university didn’t stop him. He taught himself by reading contemporary Singapore poetry. His poems are featured by Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Singapore Writers Festival, MINI Singapore, the University of Canberra and others.

The Night Is Still Young. (A Haibun)

Then and there, are here again Flashbacks The past is now the

present Memories laid to rest come back to haunt This heavy night,

sidling in the very silence A wake of sleepless thoughts “Sorry!”

I cry and cry The response is curt Sorry, echoes the Dark I regret

the chance I did not take Missing what I would never have This

chapter of my life scattered in the winds, only to surface on still

waters There is nothing I can do Time is short yet the night

is long Too quiet to sleep, I toss once more

黑夜里独白

纷乱不宁的思绪

我难以挣脱

~

– Cleo Adler (pen-name)

SEPTEMBER 27th 2021

This is an elegiac poem dedicated to the late Mr Fou Ts’ong, a renowned Chinese pianist who had been living in exile in the UK since the Cultural Revolution in China. The piece was composed as a reflection on his life and artistic practice three months after he passed away due to Covid-19.

When One Lid Closes Another Opens

Every time you played,

murmurs rumbled

from your petrified horse.

Some muffled Tuvan songs

in undertone.

You carried in your luggage

not only that voice,

but blood-stained debris

from a place that

kept falling apart,

because of which

when they admired caged

crystal flowers you sent

hooded men and women

riding on volcanoes.

At ‘home’, if so decreed,

the twin colours of keys

could flip.

What nurtured you

crushed you, from start to end.

Here, only blackness mirrors.

Between your instrument

and dilating pupils

millions of mouths chanted.

That very voice, in ‘our tongue’.

Perhaps this is a cursed tongue.

All your life you saw

a circle close.

Now that you left us,

it starts over.

In memory of Fou Ts’ong (1934-2020)

~

SEPTEMBER 20th 2021

Nicole is a diplomat and poet. All she writes describes her personal point of view and in no way represents the official position of her dear government (especially on matters of love and life). Currently stationed in Shanghai, she finds this land of beauty and history to be endlessly inspirational. Her muses are dreams…and the flowering streets of this city.

after a summer rain

this fresh scrubbed morning

buttered rays shiver

against cornflower blue

even traffic embraces

the light— silver, black, white trout

slip through capricious currents

I took my potted plants outside

yesterday at dusk, leaving

jade palms turned up waiting

to fill dew-slicked cups

night delivered on its warm promise

washing away every regret

only I forgot to let my darkness

receive this moon-lapped baptism

have the joy shaken from my leaves

~

self-portrait as an island

“let this be a moment of remembering,

my love, as I stand at the edge of myself

cliff and sea grass”

-Donika Kelly

let me describe how I understand the geography of

us—dew on hibiscus hips, rain-rippled lapis waters–

be it dawn or nightfall it is always you. you an entire

ocean and my heart a rock-strewn island– cacti

and winds hungry for green. your waves meet my

coast, pearl foam blooms at the touch of tide and

a sandstone cliff—that, my love, is us. I imagine you

taking my photograph– gulls overhead, the sun’s soft sigh

into warm stone releasing endless tones of crimson

and persimmon to the murmured mantra of blue, sway

over motion, ripple of brine and fish, a whole universe

one body…and I float, I float in you, my dear. I rise reborn

another day buoyed by the simple bliss of being…and you

shoveled from “Love Poem” by Donika Kelly

~

self-portrait as a lake

I have my seasons—

when darkness extends

deep and slow

hours thicken

to ink

a poet told me that passion can exhaust

and

I am exhausted

my ice sighs

water turning like an animal

in its burrow

white moon tracing

feathered fingers

across my midnight

as

every wave aches

for the shore

we all must break open

for the sun to warm

our wounds

listen for that breath

taken, then held deeply

as love

slipping into the silvered stillness

of a glass-covered heart

~

SEPTEMBER 13th 2021

Yuu Ikeda is a Japan-based poet. Her published poems include “On the Bed” in Nymphs, “Pressure” in Selcouth Station Press, “Dawn” in Poetry and Covid, and “The Mirror That I Broke” in vulnerary magazine. She can be found on Twitter and Instagram at @yuunnnn77, and publishes poetry on her website.

“They”

Broken heart.

Summer night.

They make harmony from madness.

Crumbled confidence.

Summer bourbon.

They carve rhythm from madness.

~

SEPTEMBER 6th 2021

Dutch, Swiss, and German, Katie Vogel has lived and worked in Shanghai for almost two years. She is a Bachata lover, fall leaf cruncher, yogi, and poet. With a B.A. in Creative Writing, her work has appeared in Parnassus, Visions, and ASPZ.

Farewell

I leave you softly

a heron listening

water cresting

bony sure knees

home grounding the heart

in morning solace

two feet never rise at once

one lingers on earth’s wet marrow

like the last friend swinging

coolly on a porch rocking chair

comfortable

the scene changes

something is not quite right

a bent cattail discolored

the kingfisher’s calculated dive

absent

new swallows nest and caw

the heron preens again

scratching the unscratchable

feeling

though all is right

perfect even

the sky is also home

and wings cannot wait for winter

~

Repatriation

There is something in silence

which shakes down trees

once planted on dusty lanes

hedged with scooters and noise

and people and life unfurling

the same velocity

waterfalls don’t know themselves

too heavy with breathing

rushing falling breaking and rebirthing

dispersing in every direction

absorbed in sky sun skin of the earth

and any human within five miles

sound rattles out of a cage

never built.

My city is far, far away.

I lay on the grass. If you zoom out,

you would see squares of earth –

sectioned portions you could fork and

eat in one bland bite.

Grass cool, I listen with all my skin:

voices from another time

race along each blade

tickling my cheek,

familiar,

packed with life.

~

AUGUST 31st 2021

Jonathan Chan is a writer, editor, and graduate of the University of Cambridge. Born in New York to a Malaysian father and South Korean mother, he was raised in Singapore, where he is presently based. He is interested in questions of faith, identity, and creative expression. He has recently been moved by the writing of Tse Hao Guang, Rodrigo Dela Peña Jr., and Balli Kaur Jaswal.

watching

waiting at the bus stop, two pull

up, departing in different roads. patrons

alight, soles on tarmac, late afternoon

hues of white or blue or green. hands

graze skin, children tugged along, screens

pocketed. the flurry weaves around my

bench, chatter blending into revved

engines. shorts and shoes move toward

the trail, cloistered between tracks and

concrete. eyes flash for a peacock or

chocolate pansy, those brilliant bursts

of orange, or the eerie dash of white,

emigrants drifting in the evening

breeze. midday flutters away, my

seat grows cold, and i dream of an

inch of another’s peace.

~

idiomatic

a small, needful brightness

worked his way through the

consonance of sunlight and

wind, at times unhurried, at

others with a turbulence like

red ants. once he faced a

cleaved road, elsewhere he

followed a stream back to

its spring. he sits in the shade

of old stories, however

atavistic, crawling with the

guilt of maternal likeness:

the silhouette of a bow,

curved as a snake, the ringing

of a bronze bell, hands cupped

over his ears, the sharpened

axe, clean through timber.

scrawled in dark ink, my teeth

begin to chatter, lips curved in

lashing strokes of red.

~

a likeness of flowers

after Wong Kar-wai

the past is something he

could see, but not touch:

years fading as if

glass had been pulverised

to grey ash, soot accumulating,

visible beyond grasp,

everything blurred and

indistinct. he yearns for all that

had left– if he could break

through that pile of

ash, return before the days began

to vanish, thumbs pressed,

anguish whispered, buried with

mud in the groove of a tree.

awakening

after Craig Arnold

to wake in the presence of

daylight, swollen eyes before

congealed lustre, sluggishly

unfurling between sorrow and

possibility. to live in the glory

of softness, before the deadened

grip of the day’s agitations, the

fumbling for a pressure valve,

a fire escape. to breathe in the nodes

of mirth, or are they a kneading

heaviness, the dull puncture of

flayed language? to see in the absence

of sequence, knife scraped against

serrated surface, the drum and rustle of

text and headline. to lean into opening

air, that sonorous exhalation,

particulate in a burnished dance. to

wake into rippling sunlight, diverting

the gaze, so tired from the gleam of

blue, to that beloved flash, that

effortless flicker. to wake in

the presence of daylight.

~

AUGUST 23rd 2021

Jonathan Chan is a writer, editor, and graduate of the University of Cambridge. Born in New York to a Malaysian father and South Korean mother, he was raised in Singapore, where he is presently based. He is interested in questions of faith, identity, and creative expression. He has recently been moved by the writing of Tse Hao Guang, Rodrigo Dela Peña Jr., and Balli Kaur Jaswal.

overnight

unwrapping a thin conclusion, as porous as

mulberry paper around a styrofoam wedge,

stained with the depth of wine, hanja and

hangul vanishing with geometric distance,

the same tremble at the edge of swallowed

disarray, darknesses as dreaded as they are

familiar, clocked around a cone of warm,

jaundiced light, circle stark on a cragged

floor, and the mind callous for the touch

of an old face, found in the frisk of a

barely lucid afterthought, fingers firm to

frost at the hem of my pants, eyes slow

to bear the witness of morning light, thin

soreness and early vision, a formal feeling

and then the letting go –

~

roadways

up the ascent of the overpass, there

is a sunset. the taxi driver gestures

for you to take a picture. his hands

are held by the wheel. a phone camera

snatches only the overlay of blues, greys,

oranges, brushed over in thick swathes.

the light shimmers over the emptied

roads. it bounces between the grilles

and beams around the workers sprawled

like cargo. an N95 dangles above the

dashboard. circuitous concrete makes for

fruitless gazing. somewhere a wish is

displaced beneath the wheels. the strain

of a load is and isn’t a metaphor. the slosh

of coffee in a flask makes for a taut

afternoon churn. hiroshima pulses

against the windows. high beams make

themselves invisible. if you wait long

enough you might see immanence and

glimmers. even if you bear some hurt

today.

~

routines

at most, condensed in the

passage of domestic life, the

few fistfuls of need, of essence

distilled in the rotary of sunrise

and dusk – the first intake of

conscious breath, the first

stream of water down the

gullet, the first sight of light-

dappled trees, the first thin

flip of ingestible verse, the

first note eased into the ears,

the first waft of coffee in a

firmly-gripped thermos, the

first moment of silence,

drawn back into calm, the

source from which all shall

return and proceed.

~

AUGUST 16th 2021

Xe M. Sánchez was born in 1970 in Grau (Asturies, Spain). He received his Ph.D in History from the University of Oviedo in 2016, he is anthropologist, and he also studied Tourism and three masters. He has published in Asturian language Escorzobeyos (2002), Les fueyes tresmanaes d’Enol Xivares (2003), Toponimia de la parroquia de Sobrefoz. Ponga (2006), Llué, esi mundu paralelu (2007), Les Erbíes del Diañu (E-book: 2013, Paperback: 2015), Cróniques de la Gandaya (E-book, 2013), El Cuadernu Prietu (2015), and several publications in journals and reviews in Asturies, USA, Portugal, France, Sweden, Scotland, Australia, South Africa, India, Italy, England, Canada, Reunion Island, China, Belgium, Ireland, Netherlands, Austria, Turkey and Singapore.

Güelga Fonda

Esti poema entamelu

nel mio maxín

fai cincu años, nel cuartu

d’un hotel de Shanghai,

Shanghai ye un llugar

que dexó una güelga fonda

na mio memoria

-un poema ye xustamente eso-.

Ye un d’esos llugares

au puedes atopar un bon poema

per cualuquier requexu de la ciudá

(o atopate a ti mesmu

nesti mundiu llíquidu).

~

Deep Mark

I started this poem

in my mind

in a room of a Shanghai hotel.

Shanghai is a place

that left a deep mark

in my memory

-a poem is just that-.

It is one of those places

where you can find a good poem

in any corner of the city

(or you may find yourself

in this liquid world).

~

JUNE 14th 2021

Chen Liwei is a member of the Chinese Writers Association, and Vice Chair of the Tianjin Writers Association. He is one of the five leaders of the Tianjin Publicity and Culture System, and was Editor-in-Chief and Senior Editor of a special edition on Chinese New Economic Literature for Bincheng Times. Chen is the author of the novels People of the Development Zone《开发区人》and Tianjin Love《天津爱情》as well as a monograph on literary theory titled ‘An Introduction to Chinese New Economic Literature’. He has published the contemporary poetry collections ‘Cuckoo in the City’《城市里的布谷鸟》, ‘The Crazy Tower’《疯塔》, ‘Dreaming About Red Lips’《梦里红唇》, ‘Life is Beautiful《本命芳菲》, and ‘Remote Sounds of Xiao’ 《箫声悠悠》, a volume of classical verse titled ‘The House on Zhen River’, and the prose collection ‘Watering Dried Flowers’《给枯干的花浇水》. In March 2016, a seminar on his work was held at the China Museum of Modern Literature.

Frog Sounds

Frog sounds – a liquid that’s deeper than a river,

blending into one as they rise and fall.

We all remember the suffocation of childhood.

For me, it was the umbrella of the moon on a summer night.

Open it when you want to hear; close it when you don’t.

Tonight I’m walking through the rugged foreign land of middle age.

I hear the sound of laughing frogs from the water,

like passing someone in another country with an accent that’s familiar.

Ask me how far away my youth is; ask me how far away my hometown is.

Ask me how far away my lover is; ask me how far is the other shore.

I have tried to answer with several books’ worth of words.

Suddenly, I realize what I’ve got in return for my efforts:

a frog jumping into the water with a plop;

frog sounds, like night. The years are as long as ever.

蛙声

蛙声是比河水要深远的液体

当它们汪洋成一片,此起彼伏

整个世界都感到童年没顶的窒息

小时候,它是夏夜月光的伞

想听时就打开,不想听时就合上

今夜我走在异乡崎岖的中年

所有水面都传来谈笑般的蛙声

像在他乡遇到的口音相似的路人

问我青春多远,问我故乡多远

问我爱人多远,问我彼岸多远

我曾尝试用几部书的文字努力回答

忽然发现,自己的努力,换来的

不过一只青蛙跃水的一声“扑通”

接下来,蛙声如夜,岁月如旧

~

Willow Flute

Playing it takes me back to childhood; I travel back to ancient times.

The wilderness strikes up a symphony of spring.

Birds lead the song; the river is the chorus; the sea is an echo.

The mountains, trees, and flowers dance together.

The sound is green, with tender buds

like golden light dancing between the conductor’s fingers.

The whole world is illuminated! The present, the past,

the world of youth, old age, and a blurred middle age.

As long as it is spring, as long as there are willows,

just a hint of long, shiny hair is enough.

柳笛

吹一声就穿越到童年,穿越回古代

整个原野马上奏响春天的交响乐

鸟儿领唱,河水合唱,大海回声

群山和所有的树木、花朵一起伴舞

这声音是绿色的,是带着嫩芽的

像是指挥家指间舞动的那一道道金光

整个世界被照亮!现在的,过去的

青年、老年、以及模糊的中年的世界

只要是春天,只要是柳树,只要

油亮的一丝丝长发,就足够了

~

Thinking About the Afterlife

However many people you meet, you will forget them all.

However many cities you visit, you will leave them all.

What most people want is a regular life, not positions of power;

generations have fought for it – a fight without swords.

Plant a flower and let it bloom as it should;

write a word, and make it clear,

for in the long afterlife, with no end in sight

you won’t necessarily plant or write

So if you get to know just a few people, you’ll remember the ones you meet;

If you visit just a few cities, you’ll fall in love with their streets.

想到来生

认识多少人,就要忘记多少人

走过几座城,就要告别几座城

人生的座位比龙椅还要抢手

一代代的争夺根本用不着刀兵

种一朵花,就让它开得干干净净

写一个字,就把它写得清清楚楚

因为在漫长的没有终点的来生

你不一定找到种花、写字的工作

因此认识几个人,就记住几个人

走过几座城,也就爱上几座城

~

Falling Leaves

You take a step and a leaf falls.

Each step you take is a gust of autumn wind.

The spring that you walked through that year has disappeared;

I went back several times but couldn’t find it.

The autumn mountain that I asked you about that year has grown old;

The inscriptions on the cliff walls have long since been stained and weathered.

From ancient times to the present, leaves have fallen all over the world –

sometimes as fast as a gust of wind;

sometimes as slow as a drop of spring water.

I came on a leaf of emerald;

I left on a leaf of gold.

落叶

你一步一片落叶

你一步一片秋风

那年走过的春天已经消失

好几次回去也没有找到

那年问过的秋山已经老去

丹崖绝壁的刻字早斑驳风化

从古至今,整个世界有落叶在飞

有时像一阵狂风那样急促

有时像一滴泉水那样缓慢

我乘一片翡翠的叶子而来

我乘一片黄金的叶子离去

~

Ironing

If you don’t iron your clothes, they’ll be full of mountains and rivers.

There are no such mountains on mine.

When I first bought this garment, it was like a newly built city:

the houses were in order, the streets were straight and clean.

Not even in the field, when it was still a skein of cotton,

did it look so pure in the autumn wind.

When do the wrinkles appear? When you’re stuck in traffic,

with the passage of time, or tangling and jostling in the washing machine…

Sometimes, with just a single glance back,

the old city collapses, taking everything with it.

With the heat of the iron, with the comfort of the steam,

the wrinkles are forced to give themselves up, or forget themselves.

Ironed clothes are smooth on the body; the mountains and rivers are flat.

The invisible bumps, only it knows.

熨衣

不熨,衣服上的山川就不平

可衣服上本来没有这些山川

刚买回时没有,那时它像一座新建的城池

房舍错落有序,街道笔直井井有条

在田野时也没有,那时它只是几朵棉花

在秋天的风中一不留神暴露了纯洁

皱褶出现在什么时候呢?路途的拥挤

时光的积压,洗衣机里纠缠、扭打……

有时,仅仅是一回眸的瞬间

曾经的城池就坍塌了,连同一切

在熨斗的高温下,在水雾的安慰下

皱褶被迫放弃自己,或主动忘却自己

熨后的衣服穿在身上山川平整

那看不见的坎坷,只有它自己知道

~

JUNE 7th 2021

Chen Liwei is a member of the Chinese Writers Association, and Vice Chair of the Tianjin Writers Association. He is one of the five leaders of the Tianjin Publicity and Culture System, and was Editor-in-Chief and Senior Editor of a special edition on Chinese New Economic Literature for Bincheng Times. Chen is the author of the novels People of the Development Zone《开发区人》and Tianjin Love《天津爱情》as well as a monograph on literary theory titled ‘An Introduction to Chinese New Economic Literature’. He has published the contemporary poetry collections ‘Cuckoo in the City’《城市里的布谷鸟》, ‘The Crazy Tower’《疯塔》, ‘Dreaming About Red Lips’《梦里红唇》, ‘Life is Beautiful《本命芳菲》, and ‘Remote Sounds of Xiao’ 《箫声悠悠》, a volume of classical verse titled ‘The House on Zhen River’, and the prose collection ‘Watering Dried Flowers’《给枯干的花浇水》. In March 2016, a seminar on his work was held at the China Museum of Modern Literature.

Tea

Some things seem like yesterday, but when you think about them too much,

they collapse, like a bubble of soap to the touch.

For years and years, the group would gather,

but many years later, their names have been lost.

Thirty years ago, a teacup was placed on a table.

Thirty years later, that teacup and table are still in my heart

but the world can no longer find their shadows –

neither the tea leaves that danced in the cup

nor the water that was brought from the yard and boiled

茶水

有些事情恍如昨日,一认真回忆

却像美丽的肥皂泡一触即溃了

很多年,很多人曾济济一堂

很多年后,很多人的名字想不起来

一只茶杯放在三十年前的桌子上

三十年后,茶杯和桌子还在心上

世界上却再找不到它们的影子

还有,那些在杯中翩翩起舞的茶叶

那些从院子里打来,并烧开的水

~

Fourteen Lines Written in Shenze

Time slows down here.

A minute is as long as a whole childhood.

A road is as long as an entire youth.

Childhood is a piece of endless white paper;

if you make a mistake, you can erase it and write it again.

Youth is a mottled palette;

when the wind blows, it sticks to the fallen canvas.

I was born here. I grew up here. I left.

A path has been hollowed out in the field.

Swimming in the blue river has turned it into a dry bed.

I rushed away from here, and took a minute –

a minute to recall my childhood; a minute to recall my youth;

a minute to slow down into a dry and distant river:

unseen waves, raging silently.

写在深泽的十四行

时间,在这里慢下来

一分钟有整个童年那么长

一条路有整个青春那么远

童年是一张无边无际的白纸

写错了什么都可以涂掉重写

青春是一块斑斑驳驳的调色板

风一吹,和倒下的画布粘在了一起

我从这里出生,长大,离开

把田间的小路走得坑坑洼洼

把蓝色的河水游成干枯的河床

我从这里匆匆走过,用一分钟

回忆童年,一分钟回忆青春

一分钟慢成一条干涸而遥远的河

看不见的波涛,在无声汹涌

~

Railsong

Parallel with the sleepers,

I count them one by one, with just one sound

and suddenly find that before and after

there are two endless distances.

A person is a sleeper

lying in the center of time.

The rails of history cannot see the beginning or the end.

One is the body, the other is the soul.

钢轨的声音

以和枕木平行的姿态

一根根一声声地数着枕木

突然发现,前后

竟有两个无尽的远方

一个人就是一根枕木

每个人都躺在时间的中心

历史的钢轨看不见首尾

一根是肉体,一根是灵魂

~

Floating Like Snowflakes

Snowflakes fall from the sky.

The closer to the ground they get, the quieter they are.

I am one of them –

stealing and carving myself with the cold.

There are more than a million possible patterns,

but I can never quite carve the one I want.

While others are blooming with dead branches,

I have already fallen to the ground and disappeared.

I am just a teardrop,

but my face was once a flower.

浮生若雪

雪花们从天上落下来

越接近地面,他们越安静

我就是其中的一朵

偷着用寒冷雕刻着自己

美丽有超过千万种图案

我却总雕不出想要的那种

人家借着枯枝怒放的时候

我早已掉到地上不见了

我只是一滴泪

虽然有过花的容颜

~

MAY 24th 2021

Jessie Raymundo teaches composition and literature at PAREF Southridge School. He is currently a graduate student at De La Salle University-Manila. His poetry has appeared in a few publications in print and online. He lives in a small city in the Philippines with his two cats.

Memory with Water

For now let’s talk about sinking

cities, said my mother

who carries a pair of Neptunes

in her eyes & paints about phantoms

in Philippine poetry. Gravity is when

the psychiatrist assessed you

& located a heart that is heavy

for no reason. In an instant, you were

in the sea: a merman sticking his head

above the surface, swathed in salt

water, standing by for austere arms,

like a remembrance possessed by echoes

of phantoms playing on a record player.

Almost always, there are greetings–

at sunrise, say hello to clouds, to roosters,

to the maps of music you made in your mind.

& when the morning arrived as a Roman

god of waters & seas, you finally crawled on land.

~

Gravity

I reread your letter & your voice

dives into my ears like shooting stars.

Words frozen, punctuation marks

like walls of a citadel.

The historic walled city where

you sketched me in a centuries-old

cathedral. I held the rosary we’d made

from old broadsheet newspapers.

The sweatier I got, the more

the beads around my wrist warped.

All statues without heartbeats

staring at you. All motionless,

rendered livelier by their staring.

More than three hundred summers ago,

Newton stared & witnessed

a heart fall out of the blue.

An aged brick, separated.

A bead detached. You’d never age

another year older. Everywhere, the devout

bending knees to the ground, saying prayers,

breathing without you. & I, too, living,

praying, motionless to adore the voice

the way I did the woman, spaces

like dust from space.

~

Bushes

Nights like these, we summon

a body, have it

abandon the wind-

down routine, the needed spindle

to prick the finger before the deep

sleep, how the curse is fulfilled:

dimming the lights, shutting the eyes

to omnipresent devices,

& if the mind begins to wander,

noticing it wandered. In front of your house,

our stomach rustling, filled

with the unseen, craving for eyes & ears.

Lola, you remember, has names

for these night noises: nuno, tianak,

sigbin. Fear not, it is just

us, the neighbors you have never

spoken with. How your fingers shiver

now, this moment with the woody stems

of your nightmares, our movements

synchronized under the spotlight

glare of the full moon.

~

MAY 17th 2021

The land I own is myself. I am dirt that became earth, and earth that became sky.

There are days when I am

so majestic, I am more spotlight than performer.

More magic than magician. And then there are days

when I wake up with my own blood in my mouth. When I am cancelled shows and empty auditoriums. When my only performance is the one-act play of getting out of bed.

On those days, I am the most epic of all superstars. On those days, I remind myself that every heartbeat

is an applause.

~

MAY 10th 2021

Yunqin Wang is a writer based in Shanghai / New York. She writes in English, Chinese, and occasionally Japanese. She has been an editor for The Poetry Society of New York. Currently, she lives in Shanghai, where she serves food at a beer bar and music at a livehouse.

Before the Ox Year Comes

Wrinkled by Manhattan air,

my orange reclines to the kitchen board

the way Ma saw me off back home.

As I walked further, her body drew smaller,

not made by the distance,

but age, fast like a blade,

without being taught,

I’ve mastered knifing the fruit.

To read in a full city the letter

you wrote in an empty house

would be cruelty. In New York,

the best park is the empty park.

What was I thinking then,

taping boxes, listing gadgets,

popping cetirizine in between,

cardboards of lives unassembled

in the slant-ceilinged loft. Two hundred

people bid for my bad vacuum.

I was giving everything a price,

parts after parts of me to nonchalant hands.

I think tomorrow, it will be the Year of the Ox.

Things still live in Chinatown:

winds, bricks, moxibustion.

Cargos swallowed up in a squall.

Gazes of satellites. Things

you can’t walk away from. Then things

that are no good on a New Year’s Eve:

you take out the trash, smashing glasses,

going to a barber. All those superstitions

assuring you how easily a good

life slips away. In the old cassette,

I recited Li Po, with a lisp, skipping lines,

I was imitating Peking operas in my raw throat,

Su San in exile, drunken concubine, and Ma

kept saying yes, yes… As long

as I kept going, she was happy.

“Once shrouded, the earth

was bitten open by a Rat. ”

This I was told by a zodiac book,

and I’m a Rat child. I think of the twelve years

traveling vessels, race-walking

in the backstreets of borrowed lights,

plucking footsteps, piling toy pistols

and foreign postals, so as to walk

on every rope on the dock of the bay.

To find the right ship. I’ve watched

gangplanks yawn and close. Mudlarks

holding onto a jade tile, and this time,

I might soon be home.

The h-mart receipts slipped

out of my basket of American dreams.

Conversations at the B7 gate. You wrote me

a recipe on this side of the continent where

the final ingredient has long been extinct. Leaves

stuck to your presbyopic glass. This first Shanghai rain.

And your letter, all safe, all sound.

(2020 NY – 2021 SH)

~

MAY 3rd 2021

Yunqin Wang is a writer based in Shanghai / New York. She writes in English, Chinese, and occasionally Japanese. She has been an editor for The Poetry Society of New York. Currently, she lives in Shanghai, where she serves food at a beer bar and music at a livehouse.

The First Dream

On the cold hospital bed, a baby’s heart

beat like a sheet of flame. Something small

and strong in an aseptic room. She arrived

on a clear Sunday morning, where jazz

is played down at the Jing’an Temple,

men lounging in bed, watching their wives

collecting mail. She arrived with an announcement,

silent like a leaf. When the doctor handed her

the first towel, it was by instinct that she knew

it had nothing to do with the crying, but a prize

for her safe landing. She learned scents.

Felt skins. Saw shapes and colors without

rushing to name, the world full of possibilities.

What came next was an earthquake. 1996

was such a peaceful year that the earth trembled

like a huge cradle. In a flash, she saw streets

reeling backwards. She heard music

in broken things, then fell asleep

like water in yet another tide.

It was the first dream of her life. And now,

20 years later, curling in the bathtub

in a shaking room in Seattle, the dream

suddenly comes alive and she realizes

whoever built the earth must have made a terrible mistake:

he must have reached for the sky to plant the first seed,

thus the world, made upside down.

The girl grew bigger each day. Along the road,

collected stones like counting clouds. Sang

to the wrens on poles ancient tales of how

they all once kinged the lands. It is with such a dream,

that the girl learned to wing, for the rest of her life,

on the earth’s vast apron.

~

APRIL 26th 2021

Nicole Callräm is a diplomat and poet. All she writes describes her personal point of view and in no way represents the official position of her dear government (especially on matters of love and life). Currently stationed in Shanghai, she finds this land of beauty and history to be endlessly inspirational. Her muses are dreams…and the flowering streets of this city.

willow

endless stretching toward water

hair moving in the breeze

disarming me

undressing the wind

and my stunned soul

music of jewels

are the staccato of rain on soil

leaf upon jade leaf

I love you

your vulnerability

this canal is fish scales in sunlight

and you

you gesture

after its movement

as though to stop the stream’s departure

as though you had something to lose

weeping

separation

single green soul

I too

know how to move

at the mercy

of heartache’s cruel flow

~

how to understand the world

copper leafed

fingers

rock a dirt cradle

……………..thick with blue flowers

………until buttercup pistils nap in sun.

I am shadow

………moss on stone

how am I to understand this world?

each tree is meditating

………petals—

………errant thoughts

………fluttering

………across pure

………blue consciousness

vines whisper

oh, sweet rot and earth

………how am I to understand this world?

green is inadequate

it’s like saying freckle

to describe the one thousand ways

light touches

your body

if there is a god

………may I leave life

………as this forest

as

………………shards of seafoam

………………dancing through honey

~

kikuzakura

the flowering tree in my garden is sublime

every flushed bough

one thousand pinched cheeks

countless kissed lips

……..sensual pink goddess

I wonder how it feels to be impeccable–

I’ve asked so many times

sitting in her perfumed

air

the only answer:

…………leaves in wind

at sunset by my bedroom window

130 impossible petals pressed against glass

I am wishing that life were this simple

that I knew when to bud and when to blossom

that I knew when I was at my peak

and everything I had to offer were self-evident

no one questions the intentions of a Sakura blossom in spring

(except for me)

I wonder what she feels tonight

each perfect

rose cup

overflowing

with liquid moonlight

does she ask what this all means?

does she see me watching her?

do her leaves hurt and sap rush when I read her this love poem?

when I sleep with her flowers scattered through my hair

does she dream of me?

~

APRIL 19th 2021

David Tait’s poetry collections include Self-Portrait with The Happiness, which received an Eric Gregory Award and was shortlisted for the Fenton Aldeburgh First Collection Prize, and The AQI, which was shortlisted for the Ledbury Forte Prize. His poems appear in Poetry Review, Magma, The Rialto and The Guardian. In 2017 he was Poet-in-Residence for The Wordsworth Trust. He lives in Shanghai and works as a teacher trainer.

The Snowline

I miss how the fields would give way to snow,

how it seemed decided between the world

and it’s watcher the exact moment

that whiteness would grow tangible.

Then fells, bright white and endless,

as if you could bow your head across the snowline

then raise it and be covered with a crown of frost,

fat icicles dangling from your beard.

I remember a farmhouse once straddling the middle

and felt jealous at the gift they’d been given,

a front door of spring and a garden of winter.

Whenever my heart walks through the snowline

I stop to listen to the whispering trees.

And I wonder if I’ll ever make it home.

~

At Tianchi Lake

There’s a small boat rowing out

from the North Korean border

and it’s the only surface movement on the lake,

too far off by far for us to hear it

the military base over there like a cabin

that can only be accessed by a slide.

The water changes turquoise in blotches

the lake a mirror of rolling clouds

and though our viewing platform teems

with crowds there’s silence, then the mist

climbs the mountain, creeps slowly towards us.

We stay for hours as it’s all we’re here for.

We stay through the rain and through the hail.

The mist comes and goes and with it the view.

We watch a hawk hunting song birds,

we watch a tour group unfurl a banner that says:

“The Number 1 Chongqing Battery Company”.

Mostly we watch vapour –

the way it climbs the far side of the mountain

then dips towards the lake, the way tendrils of mist

skirl down to the blue like souls reaching out

for the world, the shock of being taken away too soon,

of being pushed back out to the wild sky.

~

The Panorama Trick

He’s doing that trick again with his camera –

some picture of a landscape: where he’ll appear

on both the left and right sides of the picture

laughing at our mother, or pulling a face.

To us it was first rate magic, and almost incidental

were the landscapes between faces, pine forests in

Scandinavia, suspension bridges and monuments.

How does he move so fast? Does he have a twin?

The trick, like death, was to creep up behind her,

to settle in some blind spot and wait.

My mother’s hand slowly tracked the panorama

as he chuckled behind her. He’s doing it still,

but no longer emerging on the right-hand side. Our mother

keeps panning to the right, keeps waiting for him to appear.

~

MARCH 15th 2021

DS Maolalaí has been nominated eight times for Best of the Net and five times for the Pushcart Prize. His poetry has been released in two collections, “Love is Breaking Plates in the Garden” (Encircle Press, 2016) and “Sad Havoc Among the Birds” (Turas Press, 2019).

The onion smell.

my window is open.

through it

stumble words,

each holding a glass

to its chest,

with the onion smell

of hotdogs

and the sharpness

of discount

white wine. out

on the shared patio

my neighbours

are having a party. chatting

about drunken train-rides,

sex stories

and loud laughter

bright like running water. I

am inside, mean

with a mean book

and a glass of my own,

searching the silence,

too hungry to live

on the scent

of fried meat. I close my window

against any intrusion of company

and turn on the radio.

biting an apple

I light a candle

to mask that onion smell.

~

My favourite ex-girlfriend

in the pub

in a blizzard

around 2014

with james,

near to dispatch

sneaking out

when the shift

had got busy. enjoying

our beers; discussing

the job

over lunch

with a cold pint

of lager – deciding

who was hot

in the office. we were kids

I suppose, or just barely

not kids – considering work

in the light

of the schoolyard.

I mentioned

that one girl –

can’t remember

her name – made me think

of my favourite

ex-girlfriend. it was true,

I suppose, in the way

these things are –

they were both

at least blonde

and quite serious.

~

A new hat.

I buy a new hat

and a turtleneck

jumper. you also

buy jumpers,

a cardigan

and button-up

blouse. on the walk

back through town

we get two scoops

of ice cream

and sit a while,

nudging each other

whenever we see

a new dog. I am wearing

my hat – the rest

are in bags.

we can’t try them out

in this boiling

hot heat.

when we’re done

with the ice cream

we go back to the house.

something, in all this,

is happening.

~

My painting.

there are buildings

stacked in red

and textured orange,

with windows

picked ahead

in white squares.

and you can tell

it’s a view of a river

because the bottom half

is the top

made blurry

like a reflection

on the uncalm water

you get in dublin

though the buildings here are not red

they are blue,

or grey

with pessimistic eyes

horizontal slashes

done with a brush

haphazard, raised

and a shape

that could be a person

picked out

in lighter colours.

it is on my wall

near to the window

and visible from the toilet

if you don’t shut the door.

we all have things

that bring sparks in our lives

it just happens that mine

is a landscape

done in red

which looks much like dublin

if you look at it

through non-prescription

glasses.

~

MARCH 8th 2021

DS Maolalaí has been nominated eight times for Best of the Net and five times for the Pushcart Prize. His poetry has been released in two collections, “Love is Breaking Plates in the Garden” (Encircle Press, 2016) and “Sad Havoc Among the Birds” (Turas Press, 2019).

The mattress.

the building manager

works for a company

which also sells furniture.

bargaintown. they’re quite

well known, and we go in,

tell them where we live.

expect a discount

on our new mattress

and get nothing

if you don’t count

delivery.

it’s a five minute walk,

even carrying the mattress;

I could probably do it

myself. we take it

all the same. they’ve let us

have a dog – no sacrifice

on their part, but I guess

we feel we owe them. we don’t –

we pay rent. chrys

makes good money, and I

do alright. we can meet

our responsibilities – god damn

there’s nothing like it.

we can afford full price

on the mattress.

if they made us pay delivery

could afford it.

~

Dirty.

and you’re hanging out

in the hallway of your building

just because that’s where

the washing machine

- laundry;

you need clean clothes

if you want to keep your job,

keep your friends

and keep your girlfriend

happy.

a neighbour comes out

while you’re waiting.

she’s young, she’s pretty,

and she lives next door,

and walks past fast

just as you’re packing

a handful of underwear.

you say hi

and keep looking

as she opens the door

and goes out.

you’ve met her husband;

he seems nice,

even if he didn’t have a corkscrew

when you needed one.

but this

is still embarrassing;

no-one likes a girl

to know their pants get dirty.

at least, not very

early on.

~

How it was that evening.

the wind ran hard

and stampede steady,

knocking down grass

like the corners on pages

of an interesting

book. and the sky was a dull

red colour outside,

his daughter

crying, some god

or other

making rain.

~

MARCH 1st 2021

DS Maolalaí has been nominated eight times for Best of the Net and five times for the Pushcart Prize. His poetry has been released in two collections, “Love is Breaking Plates in the Garden” (Encircle Press, 2016) and “Sad Havoc Among the Birds” (Turas Press, 2019).

The safety of populated lights.

cars on the street

which settle into spaces,

heavy and hanging

as hocks of aged beef.

the windows all open

over closed shops and offices

releasing cigarette clouds

like cold morning mouths.

a woman walking quickly

to get out of a side street

and back to the safety

of populated lights. a man

feeling casual

at the door

to his apartment,

adjusting the weight

of his groceries.

~

The copper of bones

trying my hand

again at Selby Jr

in my comfortable

apartment

with its balcony

in the Dublin

northside. Last Exit

doesn’t work now –

neither does

Requiem. I first

came across them

in elbowish rooms

in Toronto and the north

end of London. something

of the copper

of bones here

I thought. something

of life – a toilet

by the stove

and four feet

from the bedclothes. and art

needs discomfort

to appreciate

properly. Selby

doesn’t function

when the water

heater does.

~

The names of plants.

reading a book

and learning the names

of various grasses,

the texture of trees

and how to tell a flower

from another flower.

nothing much like close

to the beauty

of the pasture scene

spread before us

like marmalade

scraping over bread,

but I must admit,

begrudgingly,

it does give poems

some variety.

~

FEBRUARY 22nd 2021

Originally from small town Texas, Brady Riddle currently resides in Shanghai, China, where he teaches secondary English at Shanghai American School. Brady has been recognised and awarded in various journals around the world since 2002; featured poet and presenter at writers’ conferences and poetry festivals from Houston Texas to Muscat, Oman to Shanghai, China. Most recently, Brady’s work can be found in Spittoon Collective in Beijing; A Shanghai Poetry Zine in Shanghai, China; and Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine in Hong Kong.

The Gravity of Water

“I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing …”

—J. Alfred Prufrock

I’ve carried your weight like breath

at a bottom of a sea

currents swimming in what used to be

called arterial

chewing grains of sand settled here, slipped

just behind my lips by eddying minute hands

I clear my throat and not have

a cough slip

from remnants of a castle

we didn’t build

far away enough from reactionary tides:

wood would have drifted longer